Eventually, these individual laws were combined into a single equation—the ideal gas law—that relates gas quantities for gases and is quite accurate for low pressures and moderate temperatures. We will consider the key developments in individual relationships , then put them together in the ideal gas law. We derive an equation for calculation of molecular diameter of dense fluids, with using simultaneous Lennard-Jones (12-6) potential function and the internal pressure results. The regularity is tested with experimental data for 10 fluids including Ar, N2, CO, CO2, CH4, C2H6, C3H8, C4H10, C6H6, and C6H5CH3.

These problems have led us to try to establish a function for the accurate calculation of the molecular diameter based on the internal pressure theory for different fluids. The relationship appears to hold both compressed liquids and dense supercritical fluids. The behavior of gases can be described by several laws based on experimental observations of their properties. The pressure of a given amount of gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature, provided that the volume does not change (Amontons's law). The volume of a given gas sample is directly proportional to its absolute temperature at constant pressure (Charles's law). The volume of a given amount of gas is inversely proportional to its pressure when temperature is held constant (Boyle's law).

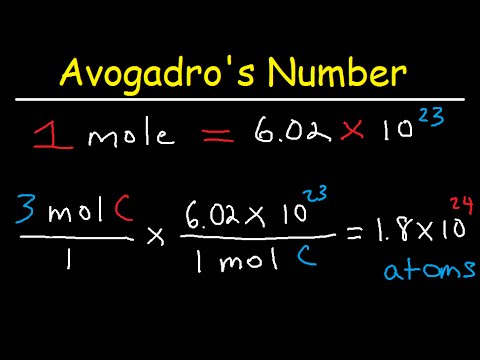

Under the same conditions of temperature and pressure, equal volumes of all gases contain the same number of molecules (Avogadro's law). Early chemists calculated the molecular weight of oxygen using the incorrect formula HO for water. This lead to the molecular weight of oxygen being miscalculated as 8, rather than 16. However, when chemists found that an assumed reaction of H + Cl \rightarrow[/latex] HCl yielded twice the volume of HCl, they realized hydrogen and chlorine were diatomic molecules. The chemists revised their reaction equation to be H2 + Cl2\rightarrow[/latex] 2HCl.

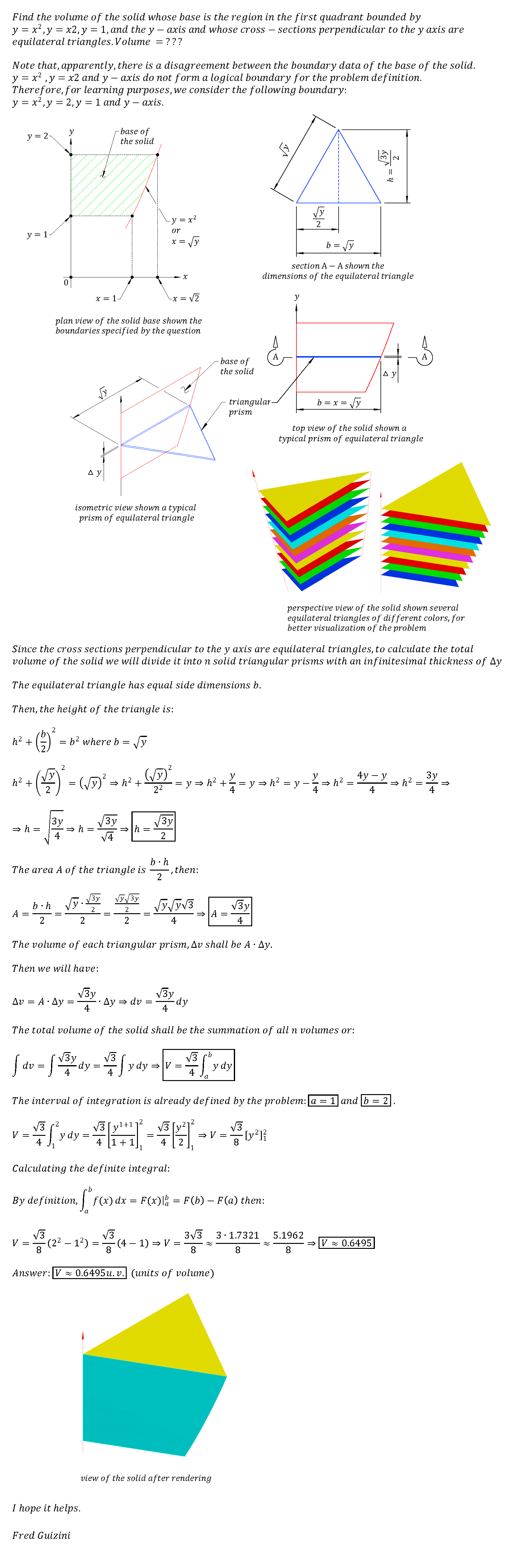

As an example, equal volumes of molecular hydrogen and nitrogen contain the same number of molecules and observe ideal gas behavior when they are at the same temperature and pressure. In practice, real gases show small deviations from the ideal behavior and do not adhere to the law perfectly; the law is still a useful approximation for scientists, however. To find a molecular formula, start by calculating the number of moles and the molecular weight of the gas using their respective formulas. Then, add together the atomic weight of each of the atoms in the formula, which you can find using the periodic table.

Next, divide the molecular weight by the empirical formula weights to come up with a ratio. Finally, multiply the entire empirical formula by this ratio to yield the molecular formula. But why should attractive interactions have this effect; why should the pressure of the real gas be less than that of the hypothetical ideal gas? Perhaps the best way to develop a qualitative picture is to recognize that attractive intermolecular forces tend to cause the gas molecules to clump up. After all, it is these attractive forcesattractive force that cause the molecules to aggregate to a liquid at low temperatures. Since the volume occupied by the gas is dictated by the size of the container—not by the properties of the gas itself—this clumping-up tendency finds expression as a decrease in pressure.

This relationship between temperature and pressure is observed for any sample of gas confined to a constant volume. An example of experimental pressure-temperature data is shown for a sample of air under these conditions in Figure 9.11. Gases whose properties of P, V, and T are accurately described by the ideal gas law are said to exhibit ideal behavior or to approximate the traits of an ideal gas. An ideal gas is a hypothetical construct that may be used along with kinetic molecular theory to effectively explain the gas laws as will be described in a later module of this chapter. Although all the calculations presented in this module assume ideal behavior, this assumption is only reasonable for gases under conditions of relatively low pressure and high temperature. In the final module of this chapter, a modified gas law will be introduced that accounts for the non-ideal behavior observed for many gases at relatively high pressures and low temperatures.

Say that we want to calculate the molecular weight of water. The molecular weight is the sum of the atomic weights of the atoms in the molecule. Then we write down how many of each of these atoms the molecule contains, which, in the case of water, is 2 and 1. Molecules are composed of several atoms, for example a carbon dioxide molecule is made up of 1 carbon atom and 2 oxygen atoms. The molecular weight (or molecular mass or relative molecular mass ) is the sum of the atomic weights of all the atoms in the molecule.

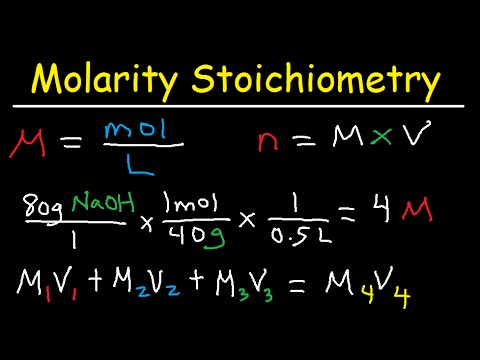

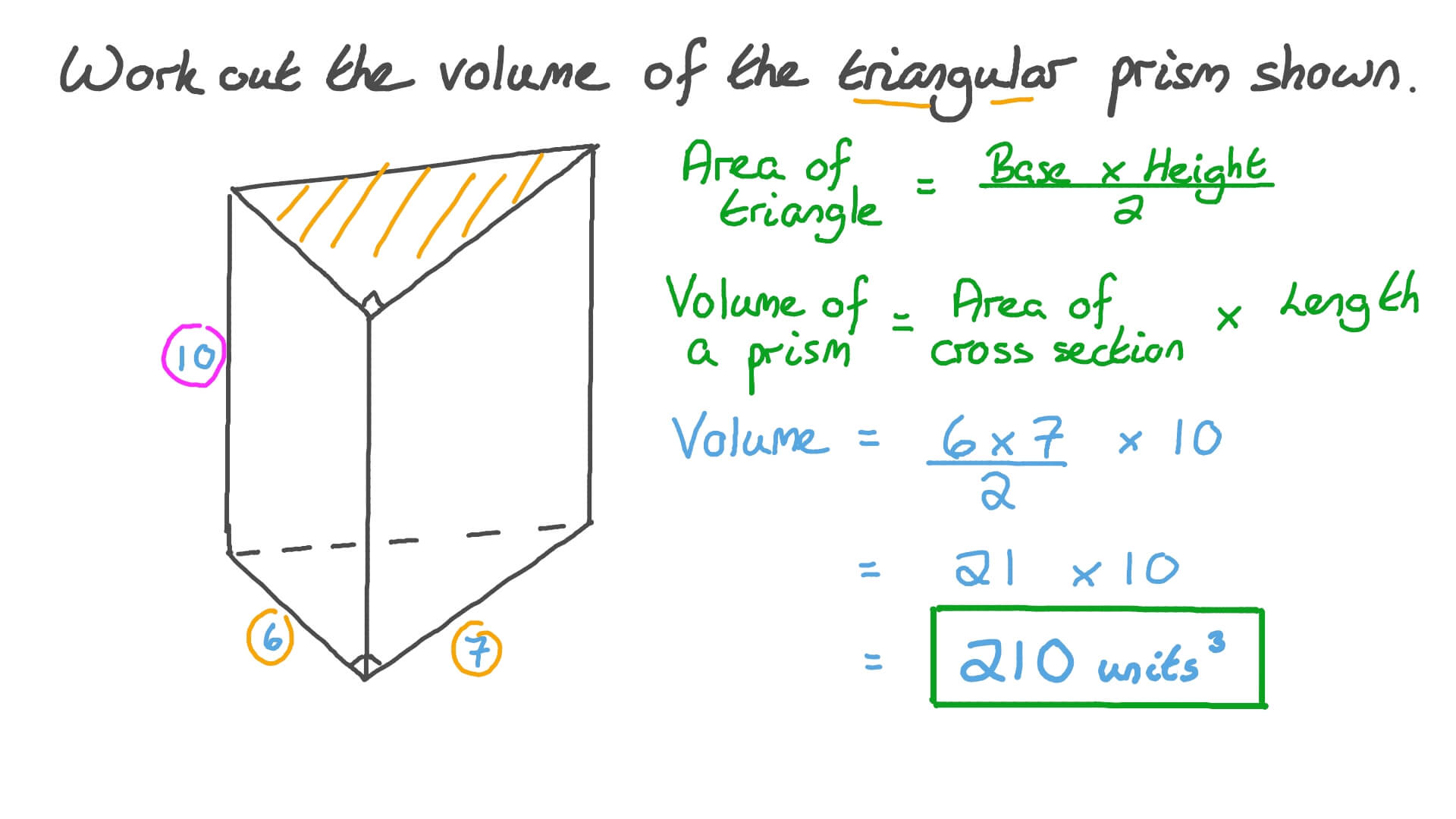

Calculations involving the mole can be used to determine unknown concentrations, volumes and masses in reactions. One mole of any gas occupies 24 cubic decimetres at room temperature and pressure. Is the volume occupied by one mole of a chemical element or a chemical compound. It can be calculated by dividing the molar mass by mass density (ρ).

Molar gas volume is one mole of any gas at a specific temperature and pressure has a fixed volume. One mole of any gas occupies the same volume when measured under the same conditions of temperature and pressure. In this experiment, the volume of one mole of hydrogen is calculated at room temperature and pressure. First convert this volume into mass using density (g/mL), then convert grams to moles using the molecular weight. Again, include units and set up your calculation so that milliliters and grams cancel in the calculation leaving an answer that has units of moles.

Avogadro was an Italian Physicist who first described the Avogadro constant as a hypothesis in 1811. He was trying to understand why in chemical reactions involving gases the observation that equal volumes of different gases had the same number of moles. This was found true even when the masses were very different. The idea that a mole of any substance has exactly the same number of atoms no matter what the substance is made of was explained by Avogadro and his name has stuck to his number ever since. The molecular weight is the mass of one mole of a substance.

In this movie, we show how to calculate the molecular weight of a substance from the atomic weights given on the periodic table. On another page, we use the molecular weight to convert between the macroscopic scale and the microscopic scale . This ideal gas law calculator will help you establish the properties of an ideal gas subject to pressure, temperature, or volume changes.

Read on to learn about the characteristics of an ideal gas, how to use the ideal gas law equation, and the definition of the ideal gas constant. Therefore, the internal pressure was used to calculate the molecular diameter of quite different fluids for which the reliable experimental values are available. The calculated and experimental values of molecular diameter are found to present a close agreement with each other. It will have become clear that the difficulties in a statistical-mechanical treatment of pure fluids are greatest at low temperatures and high densities, that is, in the liquid region. Several models of the liquid state have been developed which provide approximate methods for calculating properties and which have some utility as bases for empirical correlations.

Lattice-cell models represent one class of such theories. As the name implies, these theories are rather similar to those that might apply to the solid state, where the molecules spend most of the time at or near one location in the volume of the assemblage . Despite the fact that the description of dense fluids at the molecular level is very complicated, they obey some relatively simple rules .

Among these, we may refer to , the Taite equation that was presented by Tait about 100 years ago, the linearity of the bulk modulus versus pressure for each isotherm. In the gas phase, molecules are far apart; in the liquid or the solid phase, they are packed together. At its boiling point, the volume of a liquid is much less than the volume of the gas from which it is condensed. At the freezing point, the volume of a solid is only slightly different from the volume of the liquid from which it is frozen, and it is certainly greater than zero. These commonplace observations are readily explained by supposing that any molecule has a characteristic volume. We can understand this, in turn, to be a consequence of the nature of the intermolecular forces; evidently, these forces become stronger as the distance between a pair of molecules decreases.

Since a liquid or a solid occupies a definite volume, the repulsive force must increase more rapidly than the attractive force when the intermolecular distance is small. Often it is useful to talk about the molar volume of a condensed phase. By molar volume, we mean the volume of one mole of a pure substance. The molar volume of a condensed phase is determined by the intermolecular distance at which there is a balance between intermolecular forces of attraction and repulsion. It fits pressure-volume-temperature data for a real gas better than the ideal gas equation does. The improved fit is obtained by introducing two parameters (designated "\(a\)" and "\(b\)") that must be determined experimentally for each gas.

Van der Waals' equation is particularly useful in our effort to understand the behavior of real gases, because it embodies a simple physical picture for the difference between a real gas and an ideal gas. The volume and temperature are linearly related for 1 mole of methane gas at a constant pressure of 1 atm. If the temperature is in kelvin, volume and temperature are directly proportional. Charles's law states that the volume of a given amount of gas is directly proportional to its temperature on the kelvin scale when the pressure is held constant.

Two solutions that have the same molarity will have the same number of molecules of the chemical per liter but are likely to contain differing masses of that chemical per liter to achieve this. Whereas two solutions at the same concentration will have the same mass of the chemical per liter of solution but are therefore likely to have differing numbers of molecules of that chemical per liter. Provided some additional information is known, one value can be deduced from the other using the equations below. And even to estimate molecular weights, and there are many reports of such studies in the literature, as highlighted in the following section. Know the relationship between molecular and empirical formulae. The empirical formula provides the simplest, most reduced ratio of elements within a molecule, for example, two oxygens for every carbon.

The molecular formula tells you how many of each of those atoms is present in the molecule. The two formulae are related by a whole number ratio such that if the empirical formula is multiplied by the ratio, it will yield the molecular formula. This online calculator you can use for computing the average molecular weight of molecules by entering the chemical formulas (for example C3H4OH3 ). Or you can choose by one of the next two option-lists, which contains a series of common organic compounds and all the elements.

The molecular mass calculator will recognize the entered formula's, which are included in the list of organic compounds. Examples and practice problems of solving equation stoichiometry questions with gases. We calculate moles with 22.4 L at STP, and use molar mass and mole ratios to figure out how many products or reactants we have. The most common molar volume is the molar volume of an ideal gas at standard temperature and pressure (273 K and 1.00 atm). • To calculate the molecular weight of a molecule, simply add up the masses of the individual atoms. The molecular parameters are particularly useful in determination of molecular structure.

Qualitatively, nature of molecule has been indicated by molecular diameter at given temperatures. In this paper, the internal pressure has been used to calculate molecular diameter. By use of the temperature dependence of internal pressure parameters, the molecular diameter has also been calculated at each temperature.

In this paper, we have also shown that internal pressure is closely related to the molecular diameter. Regularities, which were originally devised for normal dense fluids, are based on the cell theory and consider only nearest adjacent interaction. Regularities are applied well to Lennard-Jones fluids which their interaction potential can be modeled rather accurately by the (12-6) powers of inverse intermolecular distance.

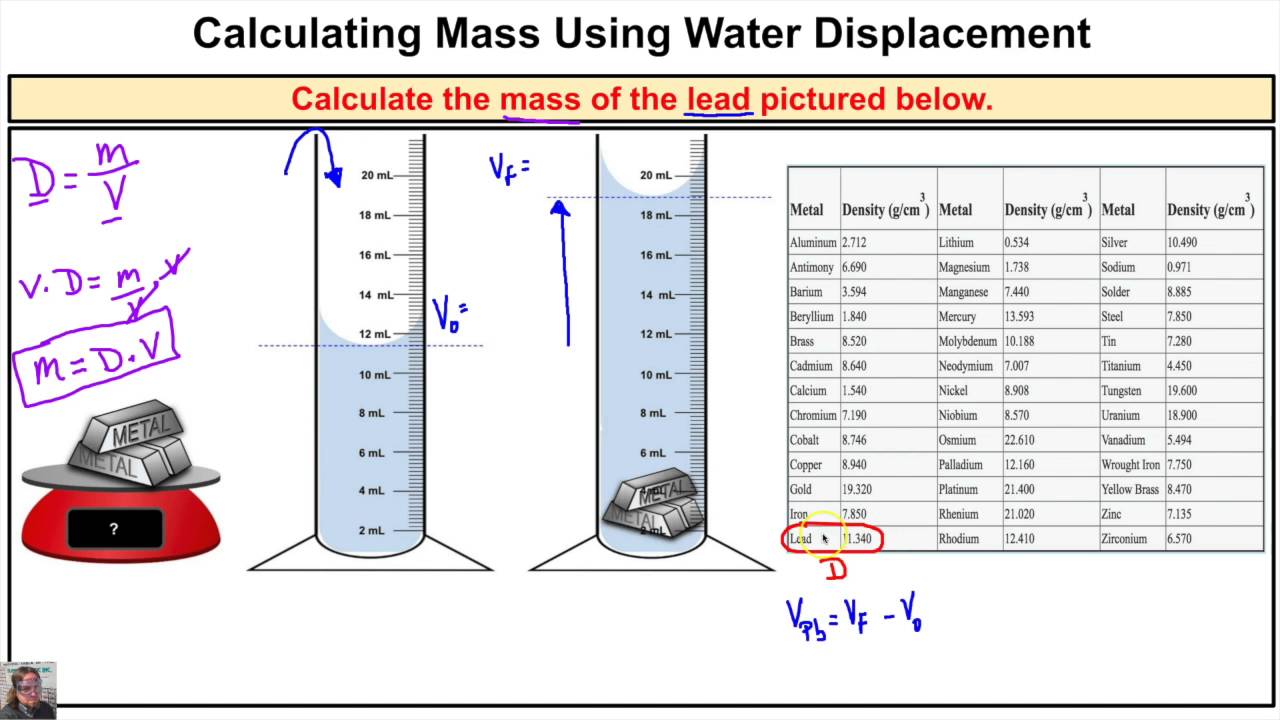

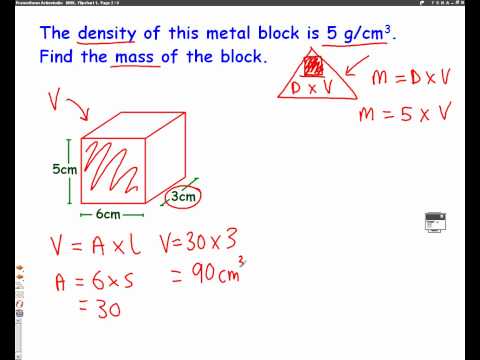

Lennard-Jones potential function suitably describes the interactions between the molecules of a fluid under the condition that it behaves as a normal fluid. These regularities were attempted to calculate the thermodynamic quantities by modeling the average configurationally potential energy and then taking its derivative with respect to volume . This means equal amounts of moles of gases occupy the same volume under the same conditions of temperature and pressure. What two things do you need to know in order to find the density of water? Students should realize that they need both the volume and mass of a sample of water to find its density. Suggest that students use a graduated cylinder to measure volume in milliliters.

Suggest that students use a balance to measure the mass in grams. Tell students that they can find mass by weighing the water. However, since water is a liquid, it needs to be in some sort of container.

So in order to weigh the water, they have to weigh the container, too. Explain to students that they will have to subtract the mass of an empty graduated cylinder from the mass of the cylinder and water to get the mass of just the water. In particular, the existence of diatomic molecules of elements such as H2, O2, and Cl2 was not recognized until the results of experiments involving gas volumes was interpreted. The interest stems from that accurate measurements of the unit cell volume, atomic weight and mass density of a pure crystalline solid provide a direct determination of the Avogadro constant. We can use the ideal gas equation to calculate the volume of 1 mole of an ideal gas at 0°C and 1 atmosphere pressure.

You should then calculate the empirical formula weight. Then, divide the molecular formula weight by the empirical formula weight. This answer gives you the number you'll need to multiply the subscripts in the empirical formula to get the molecular formula. You can double check that you got the right answer by calculating the molecular molar mass of the molecular formula you calculated. A temperature difference in the free-molecule gas causes a thermomolecular pressure difference that drives the vanes.

The radiometer will stop spinning if enough air leaks into its glass envelope. (It will also stop spinning if all the air is removed from the envelope.) The flight of objects at high altitudes, where the mean free path is very long, is also subject to free-molecule effects. Such effects can even occur at ordinary pressures if a significant physical dimension becomes small enough. Important examples are found in many chemical process industries, where reactions are forced by catalysts to proceed at reasonable speeds. Many of these catalysts are porous materials whose pore sizes are smaller than molecular mean free paths.

The first is that the lengths involved, especially the mean free path, are minute compared with ordinary lengths, even with the diameter of a capillary tube. This means that gas behaviour and properties are dominated by collisions between molecules and that collisions with walls play only a secondary role. The second is that the mean free path is much larger than the molecular diameter. Thus, collisions between pairs of molecules are of paramount importance in determining ordinary gas behaviour, while collisions that involve three or more molecules at the same time can basically be ignored. • To convert volume to moles, first convert to mass using density, then convert to moles using molecular weight.

Again, be sure to include all units in your calculations. The precise meaning of the internal pressure is contained in a generalized manner in the following well-known thermodynamic equation. United forces of external and internal pressure equalize the thermal pressure which tries to expand the matter. If the internal pressure of a fluid is available, then the molecular diameter can be calculated easily. The main objective of the present research is to compute the molecular diameter. If the equation holds, determine the temperature dependences of the molecular diameter.

The results of these calculations are also compared with other calculations which obtained using the statistical mechanical theory for calculation of molecular diameter. This equation is read as 2 moles of sodium hydrogencarbonate decomposes to give 1 mole of sodium carbonate, 1 mole of water and 1 mole of carbon dioxide gas. The equation is read as 1 mole of calcium atoms reacts with 2 moles of hydrochloric acid to form 1 mole of calcium chloride salt and 1 mole of hydrogen gas molecules . To recognize that real gas molecules both attract and repel one another, we need only remember that any gas can be liquefied by reducing its temperature and increasing the pressure applied to it. Now, two distinguishing features of a solid are that it retains its shape and that it is almost incompressible.

We attribute the incompressibility of a solid to repulsive forces between its constituent molecules; they have come so close to one another that repulsive forces between them have become important. To compress the solid, the molecules must be pushed still closer together, which requires inordinate force. On the other hand, if we throw an ice cube across the room, all of its constituent water molecules fly across the room together. Evidently, the water molecules in the solid are attracted to one another, otherwise they would all go their separate ways—throwing the ice cube would be like throwing a handful of dry sand. Water is made from 2 atoms of hydrogen and 1 atom of oxygen. A mole of water molecules would be 2 moles of hydrogen atoms plus 1 mole of oxygen atoms.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.